和三盆や練りきりなど和菓子をつくるために使われる菓子木型をつくる職人は、全国的にもとても数人と貴重な存在で四国では市原吉博さんただ1人しかおりません。そんな市原さんの工房を訪ねました。菓子木型を使って和三盆作りが体験できる『豆花』もあわせてオススメです。

Reflecting the four seasons, the wooden mold typically used to form Japanese sweets is a Japanese traditional craft. The formative beauty leads to growing demand for their ornamental use. In recent years, the wooden molds have also attracted attention from other industries. However, the number of craftsmen capable of making them is decreasing. We visited the only craftsmen in Shikoku, Mr. Yoshihiro Ichihara, who has a studio in Takamatsu.

Workshop space “Mamehana”.Bookings for a workshop (conducted in English) with Ayumi Uehara need to be made in advance by phone or email. See www.mamehana-kasikigata.com/english. The price is ¥1000 per person and includes the sweets you make and green tea.(Experience Takamatsu)

木型工房市原 / 豆花

時間:10:00~17:00

定休:木曜日

料金:和三盆、練りきり、和三盆&練りきり(各1000円、両方の場合は2000円)

電話:090-7575-1212

メール:miya9820002000@yahoo.co.jp

住所:香川県高松市花園町1-9-13 [Google Map]

Wooden Mold Studio / Mamehana

Time : 10:00~17:00

Closed : Thursday

Fee : Wasanbon 1000yen / Nerikiri 1000yen

Tel : 090-7575-1212

Mail : miya9820002000@yahoo.co.jp

Address ; 1-9-13 Hanazono town, Takamatsu city, Kagawa pref., Japan [Google Map]

菓子木型

和三盆

道具

市原さん

豆花 mamehana

木型工房市原 / 豆花

時間:10:00~17:00

定休:木曜日

料金:和三盆、練りきり、和三盆&練りきり(各1000円、両方の場合は2000円)

電話:090-7575-1212

メール:miya9820002000@yahoo.co.jp

住所:香川県高松市花園町1-9-13 [Google Map]

Wooden Mold Studio / Mamehana

Time : 10:00~17:00

Closed : Thursday

Fee : Wasanbon 1000yen / Nerikiri 1000yen

Tel : 090-7575-1212

Mail : miya9820002000@yahoo.co.jp

Address ; 1-9-13 Hanazono town, Takamatsu city, Kagawa pref., Japan [Google Map]

TAKAMATSU’S SWEET TRADITION: EXPERIENCE THE ART AND CRAFT OF WASANBON

Walking into Yoshihiro Ichihara’s workshop in downtown Takamatsu, your senses are immediately struck by the delicate, almost sweet scent of freshly worked wood. Then your eyes take over. Chisels large and small litter the main workbench where Mr. Ichihara sits, in jeans and a checked shirt, carving the initial outline of a maple leaf into a small rectangular slab of wood. On a bench behind him are several small machines; a mix of fixed drills, sanders and lathes. Another is home to a small collection of hard-looking, bite-sized pink and white sweets, some shaped like flower heads, others depicting the faces of cartoon-like characters.

Even in a nation renowned for the breadth, depth and quality of its traditional artisans as Japan, Mr. Ichihara is a rarity. The septuagenarian is the last person in Western Japan handcrafting the wooden molds (called kashikigata) used to make a type of sugary sweet called wasanbon, a traditional accompaniment to green tea that shares its name with the fine-grained sugar used to make it.After decades spent perfecting his craft, Mr. Ichihara makes chiseling intricate patterns into the kashikigata look deceptively simple, chatting away about the weather, acquaintances and anything else that comes to mind while he works.

“The smaller ones are the hardest to make. Faces, too,” he says, his thick, leathery fingers driving a chisel into the wood, as he briefly turns to talking about his craft. “It’s difficult to make such fine details. The bigger molds look more striking, but they are actually easier to make.”

FROM WOOD TO WASANBON

Whatever the complexity, the process behind it is the same. It all begins with locally sourced 100-year-old mountain cherry wood, which after being felled is dried for two years before being cut into the basic rectangular blocks Mr. Ichihara works with. Working from a plain slab of wood to penciling on a basic design, chiseling, testing and tweaking, and then to the finished product takes an average of two days.

There’s almost nothing Mr. Ichihara cannot transform from a 2D image into a 3D mold. Step into the single-room gallery adjoining his workshop and you will see the full range of his work, kashikigata of all shapes and sizes lining shelves and filling display cabinets, from those for making finger nail-sized skull-shaped sweets to head-sized carp. There’s even a tourism poster on one wall featuring varicolored wasanbon made with Mr. Ichihara’s molds that depict a range of duty-free items – clothing, home electronics and cosmetics. And if you thought that after decades of creating so many molds Mr. Ichihara would be tiring of this task, you’d be wrong.

“I work 13 hours a day, every day, without taking holidays,” he says. “I wake up at 6:30 excited to go to my workshop. Come 9:30 at night, I start thinking, ‘oh no, I’ve only got 30 minutes left before I have to go home’. It’s not something I can imagine ever stopping.”HANDS- ON WITH SWEET TRADITION

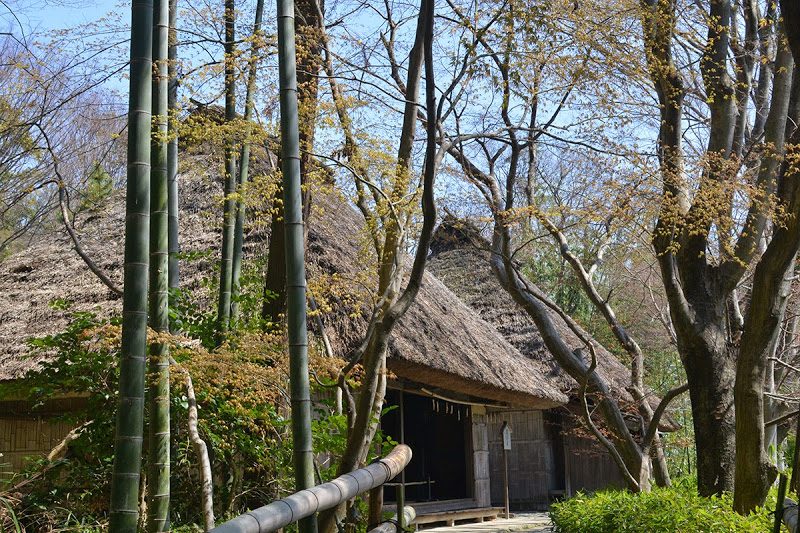

A few houses down the street from Mr. Ichihara’s workshop, his daughter, Ayumi Uehara, carries on the family wasanbon tradition with sweet-making workshops. Taught in definitively Japanese surroundings, sitting on cushions at a low table and with the English-speaking Ms. Uehara providing step-by-step guidance, the process is unexpectedly simple, but also provides rare insights into Japanese culture.

The hands-on part starts with Ms. Uehara passing you a large bowl containing a small amount of fine wasanbon sugar. Over this, you spray a little water (colored, if you like) and then squash and mix everything by hand until it starts to bind and begins giving off a soft aroma that’s almost soy sauce-like, similar to brown sugar. After sieving this, you get a light, fluffy mixture that’s ready to be tightly packed into one of Mr. Ichihara’s molds. And then it’s all done. A few sweet-loosening taps of the mold later, and you have handmade wasanbon ready to eat.

PRESERVING SHIKOKU TRADITIONS

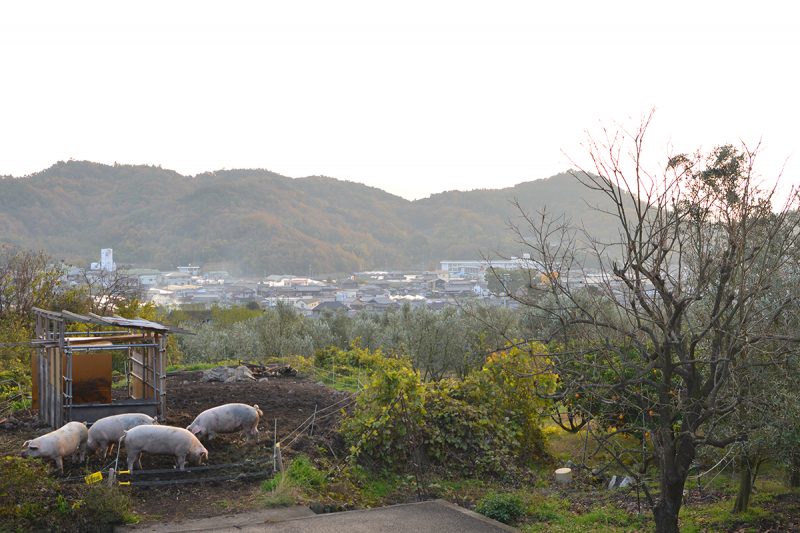

More than simply being a cooking class, the conversation during the workshop delves deeply into the roots of Japanese tea culture and wasanbon itself. Grown mainly in Shikoku, in Kagawa and Tokushima prefectures, Ms. Uehara explains that the high-grade wasanbon has been an integral part of making wagashi (traditional Japanese sweets) since the Edo era, the sugar’s sweetness and faint aroma creating the perfect counterpoint to the creamy bitterness of green tea.

“Wasanbon is inseparable from tea and court culture. In old Japan, where there was a castle, there’d be tea culture around it, and with tea culture there’d be wagashi,” Ms. Uehara explains. “Kashikigata and wasanbon have a long history, but today there are very few people making traditional molds. My father is one of the last. Many of the wasanbon you buy in supermarkets around Japan nowadays don’t use pure wasanbon sugar either – it gets mixed with standard granulated sugar – but you can still find real wasanbon in Shikoku.”

And Ms. Uehara makes sure you can still try real wasanbon the traditional way: served with tea. As the workshop draws to an end, she whisks up a cup of frothy matcha green tea, which she serves in a ceramic cup alongside an urushi lacquerware plate on which are arranged a mixture of just-made and several-day-old wasanbon.Freshly made, the sweets melt as soon as they touch the tongue, hitting the taste buds with an intense sweetness before becoming creamy and rich. Then it’s a study in contrasts, with a sip of rich, bitter tea followed by a sampling of wasanbon that have been left to harden for a few days (three days to a week is the standard waiting time). The latter almost threatens to break a tooth before the wasanbon cracks in half and releases its creamy sweetness – a flavor that has probably changed little over the centuries, and one that Shikoku is still rightly proud to call its own.

![【高知】魚を守る道、アイスハーバー型らせん魚道 – [Kochi] Ice Harbor type spiral fishway](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/wordpress-popular-posts/50244-featured-120x120.jpeg)

![【香川】春日川の川市 – [Kagawa] River market of Kasuga river](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/wordpress-popular-posts/49605-featured-120x120.jpeg)

![【香川 8/4-6】真夏の夜の夢2023 in マザーポート高松 - [Kagawa] Setouchi Summer Festival](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/wordpress-popular-posts/51118-featured-120x120.jpg)

![【日本唯一 徳島】水銀朱の採掘遺跡『若杉山辰砂採掘遺跡』 – [Tokushima] Mercury vermillion mining site “Wakasugiyama Cinnabar Mining Site”](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/shinsha_cinnabar-lacquer_red-stone-800x533.jpg)

![【尾道】日本初!自転車に乗ったままチェックインできるサイクリスト専用ホテル『ホテル サイクル』 – [Onomichi] HOTEL CYCLE](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/CYCLE-HOTEL-800x534.jpg)

![【香川】城山不動の滝 – [Kagawa] Mt. Kiyama Fudo waterfall](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/kiyama-fudo-waterfall-01-800x533.jpg)

![【香川】古くからお遍路さんの喉を潤してきた桃『飯田桃園』 – [Kagawa] Plum and Peach orchard “Īda Peach Farm”](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ida-peach-farm-800x533.jpg)

![【香川】ことでんでお花見。挿頭丘駅(かざしがおかえき) – [Kagawa] Kazashigaoka station of Kotoden](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/kazashigaoka-sakura-kotoden-800x533.jpeg)

![【香川 10/12-2/2 生誕120年!!】香川をデザインした男、和田邦坊「灸まん美術館」 – [Kagawa 12th Oct. – 2nd Feb. ] Works of Kunibo Wada, 120th Anniversary](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/kunibo-wada_kyuman-museum-800x407.jpg)

![【国の登録有形文化財】国際文化会館 – [National register of tangible cultural properties] International House of Japan](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/panorama_International-House-of-Culture-04-800x533.jpg)

![【香川 10/9-11】讃岐に秋を告げるこんぴらさんの神輿渡御 『金刀比羅宮例大祭』 – [Kagawa 9-11 Oct.] Konpira Shrine Autumn Festival](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/konpira-shrine-festival_00-800x600.jpg)

![【香川 4/12-30】樹齢800年の孔雀藤。香川県高松市の岩田神社 – [Kagawa 4/12-30] Peacock Wistaria at Iwata shrine](https://yousakana.jp/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ishida-shrine-800x534.jpg)

0 Comments

1 Pingback